Red wine production. Do you know how red wine is made?

The fleshy, juicy berries of a bunch of Refosco dal Peduncolo Rosso or Schioppettino or other varieties have very light green flesh. But the wine obtained displays a ruby red colour or some similar hue, which depends on the grape variety and maceration times.

Why does this happen?

The reason is very simple. Red wine production first of all involves destemming, in other words the removal of the stalk, which contains bitter and herbaceous substances that would compromise the elegance of the wine. The grapes are crushed and pressed to release the pulp and juice (must), which becomes coloured due to contact with the skins. The skins, in fact, contain anthocyanins and tannins. Both are responsible for giving wine its colour; the tannins also contribute to its structure, stability and give the tactile sensation of astringency typical of red wine.

The aromas found mostly in the skin, but also in the flesh, also transfer quickly into the must with pressing.

Summary

Maceration

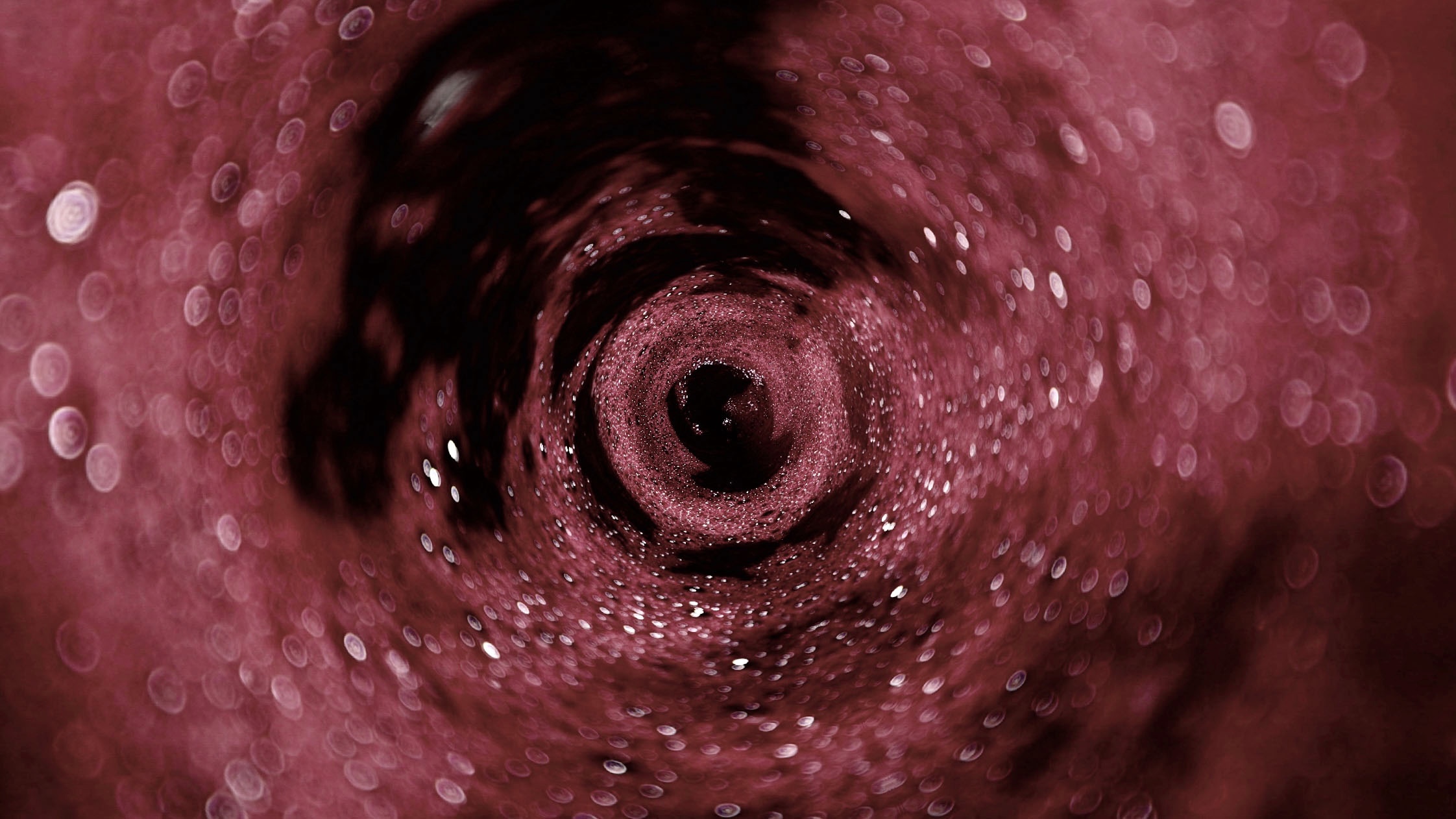

The contact phase between solid parts and liquid is called maceration, and it is here that we see the first important difference between red and white wine production.

Maceration may be long or short, depending on the wine to be produced. Short macerations (a few days) give fruity, fresh wines, not deeply coloured, and moderately structured. Long macerations (20-30 days) give more richly coloured wines, rich in tannins and structure, destined for medium-long ageing.

Alcoholic fermentation

The must is pumped into the vinification vats, with yeasts then added. The start of alcoholic fermentation is signalled by the typical bubbling caused by the production of carbon dioxide. The protagonists in this phase are yeasts, which transform the sugars present in the must into carbon dioxide, alcohol and hundreds of substances that form the structure of the wine and its aromatic content.

As this gas develops, it tends to evaporate from the must, dragging the substances it encounters upwards. As a result, a solid layer (composed of skins and other substances, and called pomace) collects and floats on top of the surface of the must turning into wine beneath; this is known as the cap.

The cap, pumping over and délestage

Exposure to the air of the upper part of the cap can trigger oxidation and acetification processes. To avoid this, punching down (i.e. breaking the cap) and pumping over are carried out using pumps, bringing the liquid from the bottom to the top to keep the pomace moist. This optimizes extraction of the elements present in the skins (e.g. colour, aromas, flavour compounds), as well as oxygenating and reinvigorating the yeasts.

During red wine production, délestage is also carried out, in which the liquid is transferred from one vat to another. In this way the cap comes to rest on the bottom of the original vat, where it tends to compact. After a few hours the must-wine is pumped over the cap again. This operation is carried out in order to slightly aerate the liquid and encourage the complete transformation of sugars, and to remove the grape pips.

The temperature of red wine production

Controlling the temperature during the fermentation process is essential to avoid interruptions in fermentation, which could compromise the quality of the wine. To avoid this danger, it is stabilized between 28 °C and 30 °C.

Racking

At the end of fermentation, in a process known as “racking”, the wine is separated from the pomace, which, still soaked in precious liquid, is pressed to extract wine rich in colour, tannins and extract.

At the end of fermentation, in a process known as “racking”, the wine is separated from the pomace, which, still soaked in precious liquid, is pressed to extract wine rich in colour, tannins and extract.

Racking is performed by slightly aerating the wine in order to encourage the complete transformation of the sugars. The cap falls to the bottom of the tank and the wine is poured into another container to complete the alcoholic fermentation and await malolactic fermentation. This transforms malic acid (acerbic acid) into lactic acid, resulting in wine which is softer on the palate.

Clarification

The last phase consists of clarifying the wine with the use of fining agents or envisaging a period of slow resting to remove the elements that cause slight turbidity.

Pomace for distillation

The pomace, still soft and fragrant, is destined for distillation. to produce grappa.